It starts out small enough. Your vision seems slightly blurred. At first you just think it’s a sign of increasing age; you notice that reading text is a little harder. But after a few months it seems to get worse. Eventually you go to your doctor, and he refers you to an ophthalmologist. After hearing your symptoms, the ophthalmologist sighs and asks if you have a history of diabetes. When you say you do, he says that he has to do an exam, but he’s sure that it’s diabetic retinopathy and it’s already in its most advanced phase.

He goes on about laser therapy and vitrectomy and possible drug therapy, but you only hear part of it. What happened? How could your eyes have become so affected without you knowing it? Will you be doomed to go blind?

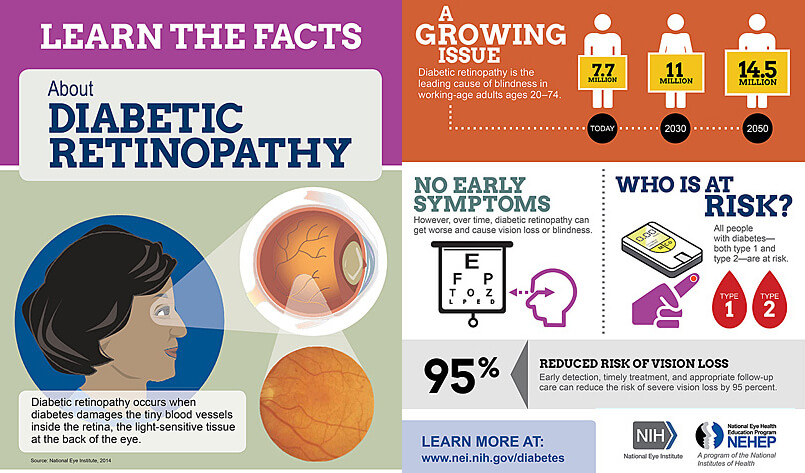

That’s the curse of diabetic retinopathy; there are often no symptoms until it is in an irreversible phase. The early cases are much more easily treated, but the symptoms that cause most people to go to the doctor aren’t present yet.

“curse of diabetic retinopathy; there are often no symptoms until it is in an irreversible phase.”

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is the term for all damage to the retina in cases of diabetes. It’s caused by damage in the small blood vessels in the retina. Almost every diabetic, whether type one or two, will have some case of it in their lifetime. Eighty percent of diabetic patients will have symptoms, and it’s responsible for twelve percent of all cases of blindness in the US each year. The first form of the condition, background (also called nonproliferative) retinopathy, usually does not have obvious symptoms. It has three phases: mild, moderate, and severe. If allowed to progress, it will go into the more severe proliferative retinopathy. That progression is associated with various symptoms, such as blurred vision, seeing double, difficulty reading, spots or floaters in the field of vision, and loss of peripheral vision. A related condition, macular edema, the build up of fluid in the macular region of the retina, is associated with fifty percent of diabetic retinopathy cases. It usually worsens symptoms of retinopathy, but can also cause separate complications. The most common symptom of this is a feeling of pressure in the eye and blurred vision.

“DR is the biggest cause of blindness in the 20 to 64 age group. And almost ninety percent of those cases could be prevented.”

What could prevent vision loss and blindness? Reliable early screening. The American Diabetic Association recommends that all diabetics get a dilated eye exam once a year. Not every diabetic goes for a yearly screening. It’s estimated that thirty percent of diabetics do not get routine eye screens. Why do some people not go for a screening? For one, it’s something that’s easy to miss, since the connection between diabetes and eye problems isn’t immediately obvious. When blood sugar levels are well-controlled, diabetes is considered managed, and virtually all complications associated with it are less frequent. And while that’s true to a degree even with diabetic retinopathy, it is one of the complications almost all diabetics get. (In fact, sometimes a greater control over blood glucose levels can actually lead to worsening of retinopathy that’s already there!) In the US, patients don’t get screened because their health insurance doesn’t cover exams from ophthalmologists. Medicaid doesn’t cover those, and older diabetic patients are the ones that are most likely to have the complications.

A dilated eye exam is a multi-part exam where all regions of the eye are examined for abnormalities. An eye chart is used to detect visual acuity. Drops are placed in the eye to dilate it and reveal general abnormalities of the retina. After that, an ophthalmoscope will be employed to examine the retina in greater detail. In some cases, a fluorescein angiogram will be done, where a fluorescent dye is injected into a vein and the retinal blood vessels are lit up by the dye, but this is only used in severe cases. If retinopathy is found, it can be treated with laser therapy. Vitrectomy, where the retina is operated on to reduce scar tissue and fluid, is used in some cases. If macular edema is involved, drugs may be injected into the area to reduce swelling.

All technologies currently in use are based on the skill of qualified eye care professionals knowing what to look for, but that may soon change. Automated DR screening software, such as EyeArt, are already producing results that are better than human graders. They can automatically identify the presence or absence of signs of DR from color fundus images of diabetic patients, thereby helping triage of patients at risk of vision loss. You can read more about EyeArt here.

References:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12766102

https://nei.nih.gov/health/diabetic/retinopathy

https://www.diabetes.org.uk/Retinopathy

http://www.diabetes.org/living-with-diabetes/complications/eye-complications/?loc=lwd-slabnav

https://www.medicare.gov/coverage/eye-exams.html

https://www.gov.uk/guidance/diabetic-eye-screening-programme-overview

http://www.diabetescare.net/authors/samuel-grossman/a-new-treatment-for-diabetic-retinopathy

http://www.who.int/diabetes/publications/en/screening_mnc03.pdf

http://www.medscape.org/viewarticle/775319

[Posted on behalf of Annie Keller]